|

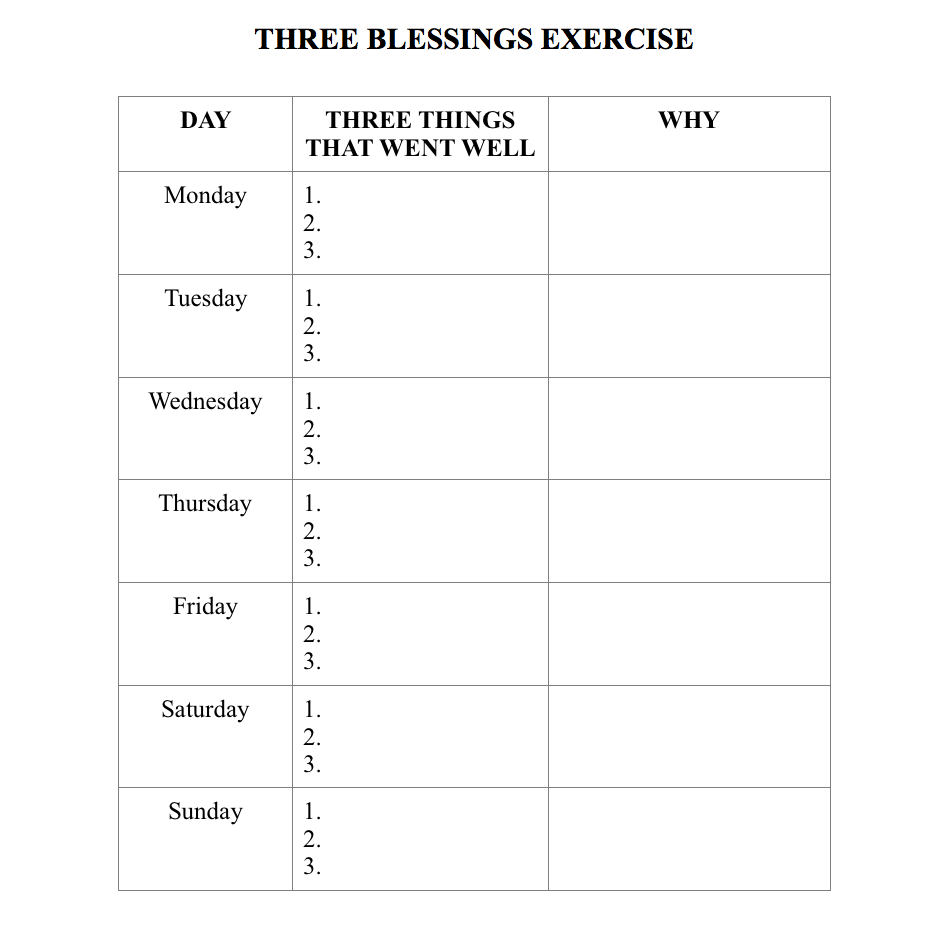

Depression is a nasty and debilitating disorder. When it is severe, there are four sets of symptoms: a chronic sad fatigue, a sense that the future is dreary, a sense of helplessness, and a loss of positive appetites. The field of psychology and psychiatry have tried to treat depression for many years with antidepressant drugs and or counselling. The success of treatments tends to be confined to moderate relief in about 65-70% of cases. Embarrassingly for our profession, placebos (that is when someone thinks they are getting a drug but are in fact getting an aspirin) have a 45-50% success rate! For those of you suffering from depressiveness, what can you do? Well Martin Seligman has just reported a fascinating piece of research, the pioneer of positive psychology, regarding what one can do to make a difference to depression. They did research on the effectiveness of completing the simplest and most uncomplicated of tasks. It was simply this: Depressed people were required to write down three things that went well that day and why they went well. That’s all. Nothing more. No counselling. No drugs. No talking. Just write down three blessings. It was called the THREE BLESSINGS exercise. They had to do it for one week. Here are the results. 50 severely depressed people participated in the study. At the end of that week 47 of them reported being far less depressed. In terms of overall happiness, 46 of the fifty people increased their happiness significantly. These results were actually better than a comparable group who took drugs or received counselling! Now before we run away with ourselves with this, there is a lot more research that needs to be done to examine the validity of these findings, but they point to something critical to everyone struggling with depressiveness. What we can learn from this is simple – there are positive and simple things you can do on a daily basis to change your mood. The THREE BLESSINGS exercise may seem hoaky, or trivial. You might, like a lot of people, justify your depressiveness by saying such things as “I am such a complicated person that a simple change wont do much for me.” “My depressiveness is very deep and a result of a lot of bad experiences, so changing is going to be very difficult for me.” Or “Things like that might wok for other people, but I am different.” Such thinking is not helpful. What we find is that major changes are a consequences of small one’s. Small changes can change big systems quite dramatically. Take the metaphor of the log-jam. You will have experienced this in traffic when one car can cause a back-up of up to a hundred cars because it has manoeuvred its way badly up Barrack Street, Blarney Street, or Sunday’s Well. However, to let the traffic flow correctly again may mean only a small change. If one car reverses a few feet and allows another one through the entire traffic jam can be released. In other words what can look like a huge traffic problem can be freed up by a small change. It’s the same with changing one’s life. One small change can have a huge effect on the flow of your emotional life. I sat with a young woman this morning that has been suffering from depression. We sat down for an hours and wrote out a list of all her goals and objectives for the next two years. At the end of our session she had a list of about 50 things she would have to do to achieve her dreams over that time. She was thrilled because when she came in she felt that there was no focus to her life, and nothing to get out of bed for. However, though it was a relatively simple task to do what I had done, this girl had never in her life taken an hour to think in a disciplined to convert her dreams into goals and to convert her goals into easy-to-do objectives. Discipline is Depression’s most feared opponent. Why not try the Three Blessings exercise and see what happens. Blue-tack a sheet of paper to your bedroom wardrobe with the following grid: Don’t be so proud or cynical to think that you are above such simplicity of living. Count your blessings. You, and they, deserve it.

0 Comments

There is an old saying that suggests that: “If you want to be happy for a few hours, get drunk. If you want to be happy for a few years, get married. If you want to be happy forever, get a garden!” The wisdom of this is in emphasising that the simplest of activities can often produce the most enduring happiness. Much of the research on the topic of happiness produces results that are not surprising but listed are a few of the more interesting findings. For example, most of us want to win the Lotto and believe that we would be much happier and content if we did. Research shows that this does not actually happen. As some of the points below illustrate, most of us have a relatively set range or happiness level that does not change too much throughout life. Our mood fluctuates form situation to situation, and may be elevated or diminished for longer periods as a result of life circumstances, but most of us return to our own base level. You will notice this with people you know - how their personalities are relatively stable and, despite life circumstances and events, they pretty much stay in character. Research shows that even the most dramatic changes often have little effects on these base levels. So, forget about pining for the Lotto, its effects would last about three months after which you would be back to your same-old self. What we can do however is to find out what we are like when we are at our best, what makes us feel good and content, and to do more of those things. Learning to be happy means learning to understand your personality, your character strengths, and those activities that bring out the best in you. Then, the formula is very simple: Use your strengths and do more of what makes you feel good. It may be as simple as gardening, taking a walk, reading a book, having a regular holiday, or concentrating on a simple hobby. So, think of activities you do that represent you at your best, at your most content and happy, and at your most vibrant. Then decide to build these activities into your life with regularity! Here are some other interesting research findings on happiness:

The moral of the research: Happiness can be taught! It should be a compulsory class in all schools – i.e. learning the science of well-being. As a psychologist, in any given day I will meet with individuals, couples, children, and families whose lives have been scarred by the tragic hand of fate - people who have been abused, neglected, grief-stricken, lonely, or traumatized by misfortune. Yet despite the fact that the lives of many people are, by any objective standards, overwhelming I never fail to be astonished by their resilience, perseverance, and optimism. “The audacity of hope”, as articulated by former President Obama, strikes the right chord in the lives of so many people during such difficult times.

“The audacity of hope” is a wonderful phrase. It highlights that hope in life requires courage. Audacity, in this phrase, illustrates that hope must be daring and bold. It implies that hope is not a weak optimism but a gutsy determination. It is as much an act of defiance as it is an act of faith. “The audacity of hope” recasts American optimism in a different light. Formerly, most Europeans have been put off by superficial American optimism through the symbols of “Have a nice day”, tinseltown, Disneyland, “mission accomplished”, and Hollywood mythology. We Irish prefer a more honest mythology. Our songs are filled with grief as much as hope. Our literary heritage is filled with stories about life that weave darkness and despair into narratives of hope and possibility from Beckett to Joyce and from Yeats to Kavanagh. We love Shane McGowan’s “Fairytale of New York” because it describes the bloodied character of life in all its tragic beauty. Luke Kelly sang as if he knew the texture of life’s hardship as much as its tender beauty. It is the responsibility of all leaders to be able to strike this chord, to find the balance between hope and despair, and courage and fear. The audacity of hope is then the willingness to salute and acknowledge the hidden tragedies of life while still remaining hopeful. As Emerson put it: “God will not have his work made manifest by cowards”. We all know what physical courage is (as seen on the field of Thomand Park every January). Mental courage in life is the willingness to look facts in the face, the ability to grasp the tragic and often meaninglessness of things in life. Without this courage the soundings of the poet, politician, or pope is restricted to cant and religious humbug! Spiritual courage is the willingness to suffer and change. The striving for the divine in life is courage. In life all of us are “made weak by time and fate, but strong in will to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield”. As people, we each seek in life the will, the audacity, and the boldness to believe in ourselves when all objective signs suggest that we may as well give in. We can so easily batter ourselves with our mistakes, failings, and imperfections and find countless reasons to fold up our tents and go home to a depressive conclusion about ourselves. But NO! We must not yield. The very essence if life is to remain audacious, is it not? To give ‘the finger’ to life’s indifference. Audacity is that which also endows us with the power to accept gratefully all that happens. To be able to bear all the brutal truths about life and yet, despite ones circumstance to remain calm and in touch with the pulse of life. This is the achievement of the heroine. Courage, the audacity of hope, is the greatest of human virtues. It is the virtue of the homemaker, housewife, working mother, single-parent, partner, lover, and single woman who, despite adversity, “picks herself up, brushes herself down, and starts all over again!” Without it the true psychological and spiritual life is not possible. When we hear of some calamity that affects our parents, our families, or ourselves our mind instantly endeavours to find some cheap compensation, something to console us for our inevitable grief, some profit in the loss. Cheap hope is without courage. Audacious hope, however, starts from an acceptance of our condition, an empathy and compassion for how hard life can be and a gratitude for the opportunity to live and to believe in… “The world which ere I was born, The world which lasts when I am dead, Which never was the friend of one, Nor promised love it could not give, But lit for all its generous sun, And lived itself and made us live”. - Arnold Fear has a very negative reputation – a reputation that is totally unjustified. Many of us spend our lives trying to rid ourselves of fear. We have demonised it so much that we are unable to see how unavoidable it is when living a full life. The truth is that it is totally impossible to live without fear. Fear, as a physical signal of danger, is essential to survive and thrive. As a parent you will recognize the eternal vigilance you have for your children. In allowing them to grow and develop their freedom (as distinct from wrapping them in cotton-wool all of their lives) your fear for them is unavoidable. “Be careful”, “Mind yourself”, “Take Care”, we all repeat endlessly to our children. The thing is, we cannot have freedom and safety at the same time. The price of freedom is to experience fear.

In seeing fear as negative we have taken a completely natural and essential human emotion and turned into something abhorrent. We have been taught from an early age that if we accept fear then bad things will happen to us. We are conditioned into believing that our fear is a reflection of our weakness, and that we should not like being afraid! We say things like: “Your not afraid, are you?” “Don’t be afraid.”. We therefore don’t like to admit that we are feeling fear! This kind of conditioning is what causes children to lie, for example. Fear is the only reason we lie. It is the only reason adults con children into thinking they should not experience fear. Life, however, is scary for children and adults. What we should be saying is “It’s all right to be afraid when something scares you”. “The bravest men in the world are also very afraid. That’s why they are heroes”. We need to teach children how to be positively afraid. We are even naturally afraid of each other in intimate relationships. Fear of your partner is ultimately emerges as an essential problem in intimacy. This is why the term vulnerability has meaning. To be open and vulnerable, to share one’s deepest feelings, one has to befriend the natural fear we all have of being hurt or misunderstood. Many men sit in my office, arms crossed, ever defiant and self-sufficient, guarded up like a fortress and stating “I am not afraid!”. Why all the armour so, I ask? We build the armour to defend against fear and vulnerability. However, it is in the acknowledgement of fear that the human heart opens to life. Love then becomes possible. Without fear, there is no love. For many men, to experience fear is to feel that there is something terribly wrong with them. So people need alcohol, affairs, aggression, domination, control, addictions, and status rather than admit to the fear that drives them. Life is both scary and wonderful. To want to get rid of fear is to want to shirk away from life itself. To banish the unwelcome guest of fear from our hearts and minds is to miss the point of living. It may sound strange, but as much as fear brings dread it equally brings joy and exhileration. Fear is the basis of courage and heroism. As long as we run from fear we can never permit the full, and yes, joyful experience of life. Joy, in fact emerges in the context of fear that is embraced and overcome. Many fun activities involve danger: Just visit an amusement park and watch the sheer delight on peoples faces on various rides and roller coasters. Small children on smaller rides – watching their faces grow through anxiety to delight. In fact excitement and thrill involves a form of delightful fear! One might say that all enjoyment involves the embracing of fear, and the relaxed surrender that follows. To fully experience joy means having come through an ordeal that has fully tested us and pushed us to the limit. “The secret of life is in knowing how to be afraid.” To be alive, to experience life in its raw intensity, to acknowledge our vulnerability, is to know fear. In knowing how to be afraid we then open a window to exhilaration, joy, and the vulnerability of love. To watch your children play at the edge of a terrifying sea is to feel fear. Yet in knowing that fear, you also know what love is. Why so? You love your children because you know that life is brief and that loss awaits all of us. Love is animated by fear and loss, and experienced as joy and wonder. All is one. When we open our hearts we can see that fear is a positive feeling of anxiety and agitation reflected in the human experiences of courage, respect, beauty, wonder, love, and joy. Everyone believes this myth: That if you know the cause of your unhappiness and what you need to do to change it you will reasonably take the steps necessary to do so.

This myth suggests to you that if you understand why you are unhappy and you know what you need to do, then that is 90% of the problem solved. It is seeing yourself as a reasonable person because, very simply, if you know what the problem is and how to solve it then you will solve it. It’s simple and makes total sense. Unfortunately this is not true. We are unreasonable people, if the real truth be known. 70% of people who have lung cancer from smoking continue to smoke! 90% of people who suffer from obesity continue to eat too much. People who get anxious because of worrisome thinking continue to worry. Though you begin to realise that this myth is foolish, it is so embedded in our thinking and logic and conditioning that it is impossible to erase it. Parents roar at their children for not being logical or reasonable, spouses engage in intense conflict over the other person’s so-called unreasonable behaviour. The real problem with unhappiness and depression is that knowing what you need to do often not make a whit of a difference because the problem is not related to a lack of knowledge or information. You will surely recognise this in yourself – that the reasons you continue to act in ways that are not really in your best interest have nothing whatsoever to do with a lack of information. You and I are emotional, symbolic, fearful, and insecure people in some many harmless ways. The reason we don’t do what we know would be good for us has to do with a number of other things other than knowledge. Our behaviour is guided by motivation, beliefs, ritual and habit, and a form of spiritual necessity. We must see the improvement of our well-being in terms of a responsibility and discipline as much as a technique. To make significant changes in one’s life one needs a mixture of desperation and inspiration mixed together. One needs some sense of immediacy, urgency, or inspiration to move and take the kind of inner and outer action you need. What stops people from actually doing what they know they need to do? What is it in you, and I, that can read a dozen self-help books and have them forgotten as soon as they are put aside? I would suggest that for many of us the fantasy of change is almost sufficient. There is a form of comforting self-soothing that occurs when you read something about what you need to do and you are able to say to yourself “Yes, that’s good. I could do that if I wanted to!” or when you say “That’s very useful information that I could use at some point…I’ll get back to it!”, “Or there is nothing new in this, I know that these are the things I need to do, and I could do them, in fact I might do them..”. And you continue to sooth yourself with the fantasy of change, with the addiction to imagined possibilities. But nothing happens. In fact the problem is more to do with a certain detachment from oneself and one’s reality that is the problem. This slight detachment allows you to then not feel any urgency, obligation, responsibility, or spiritual motivation. You detach yourself from your self and float above yourself looking down feeling sorry for yourself but void of the urgency of having to take action. Because this kind of detachment appears so intelligent it does not appear to be the impotent day-dreaming that it really is. Another reason you don’t take action is because you lack the three C’s – conviction, certainty, and commitment. To change your ways you need a strong enough reason to need to change. You need to have a sense of certainty that you are going to change, a conviction within yourself and a commitment to take action. Without this desire, motivation, and utter conviction that action is going to be taken then you are still left with nothing more than wishful thinking. There is a great deal of difference between a good intention and a committed decision. Again, there is a huge difference between someone who states that they must lose weight or get fit from someone who says that would like to lose weight or will hopefully get fit. The other reason you don’t move is that you have not really developed a clarity as to why you must change – that is your deep seated motivation for change. For this to be effective you do very often have to dig deep into your sense of responsibility and obligation to yourself or others to make changes. Alcoholics have to do this to stop drinking. The same kind of thinking has to apply to changing any bad habits or negative patterns such as anxiety or depression. All of these elements, becoming les detached from yourself, developing conviction, and being clear about why you need to change all come together into what must be a kind of spiritual discipline for yourself that is converted into ritualised action. “The world breaks everyone and afterwards some are strong in the broken places” wrote Hemingway. He is referring poetically to the fact that adversity and trauma do not break everyone. Many people grow and develop not despite adversity but because of it. “What does not kill me makes me stronger” I show the German philosopher Nietzsche put it. Or you may be familiar with Leonard Cohen’s line from “There is a crack in everything…that is how the light gets in.” Each of these people is describing the woundedness of life and how our brokenness is the essence of our humanity. The challenge of life is not to avoid adversity at all costs, but to be equal to it when it places its hand on your shoulder.

Psychological research is now supporting the intuition of these poets - that adversity makes us stronger, more robust, and fulfilled people. The erasure of adversity from life makes people weaker. We need adversity, setbacks, and perhaps some forms of trauma to reach our highest potential. If you are honest with yourself you will realise that the experiences in life that have made you a stronger and more compassionate person are experiences you would not have wished upon yourself. If you have come through a bereavement and have re-discovered your old self, doubtless your humanity has been softened, your empathy for other people has changed, and your appreciation for life in deeper. Life may not be easier, but you will find yourself to be a better parent, a better lover, a better person because of what you have been through. So our concept and understanding of how to live a meaningful life must integrate the inevitability and necessity of adversity as a pre-requisite to growth. Wisdom in life grows from the soil of suffering and it is achieved by overcoming it. Naïve happiness is built on the avoidance and denial of the woundedness and brokenness of one’s life and one’s self. Perpetually seeking good feelings, and wanting to be happy all the time, is bound to fail because it actually is avoidant of life in the round. Is it not a relief sometimes to meet someone who when you ask them how they are they do not just say “Fine” but are occasionally able to admit with an element of cheerful acceptance that they are finding things a tad difficult! If you live a somewhat stressful, worrisome, and at times hard life then this is it. The challenge is to be able to experience that as not a reflection of your inadequacy but as a reflection of the texture of all of life. If you feel inadequate then you punish yourself for not being able to cope. If you are open to the texture of life than you don’t punish yourself for being inadequate. No, you roll with the waves. What a Grateful Acceptance of all of Life. Now we must not be naïve about this either. We cannot romanticise adversity or suffering or trivialise it by saying, like mother used to say, “It’s good for you!” No one wants suffering, pain, loss, illness, death, etc. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and the effects of genuine trauma that involves a shocking confrontation with death or some overwhelming experience such as rape or battering, is awful and damaging. However, even the most awful of experiences (see Brain Keenan’s an Evil Cradling) do not destroy the person. There is an inner resilience that has great potential to overcome, though often battered, bruised, and wounded. My point is that adversity does not imply despair. And much adversity causes growth! Great Character is really about what you do with your pain. We do not receive wisdom, we must discover it for ourselves, after a journey through the wilderness which no one can make for us, which no one can spare us, for our wisdom is the unique point of view from which we come to see and experience the world. The research on adversity shows that there are times in life when adversity will be essentail to the formation of character. Major adversity is unlikely to have benefits for children although the effects of once off traumas on children are less damaging than people would tend to think. Research would suggest that adversity is best handled earlier in adult life. No one chooses adversity and no one feels that having it would make him or her any better. Yet, paradoxically, in terms of the developing fabric of human resilience and well-being it is essential to our ability to live a meaningful life. People who go through life with a silver spoon grow shallow and weak. There will be a moment in your own life when you have the opportunity to sing your Aria. In Puccini’s La Boheme Rodolpho sings to Mimi about his life – so full of passion, loneliness, love, adversity, and sweetness it is that it cannot fail to move the heart. Wonderful opera is like this, finding exquisite beauty in the midst of heartbreak and tragedy and at these moments the lead gets to sing the Aria. At this moment, the tender beauty of life is revealed to the audience. And this is life. You need to be middle-aged or over to truly appreciate opera because by this stage you have suffered and also known the sweetness of life. You know what is beautiful because of what has been tragic. Our ability to adapt to things in life is quite startling. Some experts have suggested that we live on what they term a pleasure treadmill, meaning that we continually adapt to improving circumstances to the point that we always return to a point of relative neutrality. In other words, when we repeatedly encounter the same pleasure-producing event, we experience less and less pleasure in it.

One of the most frequently cited studies of adaptation is an investigation reported some years ago by a bunch of psychologists at Northwestern University in Chicago. The researchers interviewed 22 winners of the Illinois State Lottery, which is larger in size to the national Lottery here in Ireland. Each of these lottery winners had won between a million and 100,000 dollars. The winners were asked to rate their past, present, and future happiness, as well as the pleasure they took in mundane everyday activities like talking to a friend, reading a newspaper, having a coffee break, etc. The researchers also interviewed a group of 58 individuals who had not won the lottery but lived in the same neighbourhood as the winners. The results showed that the lottery winners were scarcely happier than the comparison group in terms of their present and future happiness. On top of that, lottery winners found less pleasure in everyday activities than did non-winners. These researchers also interviewed 29 individuals who in the preceding year had suffered an accident that left one of their limbs permanently paralysed. What they found was that though their level of life-satisfaction was slightly lower than lottery winners their expected future happiness and pleasure in everyday activities were slightly higher than that of the lottery winners. These quite extraordinary results show that people have a startling ability to adapt to life events – both good ones and bad ones. The effect of positive and negative events is never as much as you anticipate. Why do we adapt? Wouldn’t it be nice if pleasure producing situations or positive life events always had the same sustained effect, if honeymoons could last forever, if winning the lotto guaranteed happiness, and if we only had to purchase one version of the Grand Turismo Play Station game. It appears that by adapting to life situations, both good and bad, it protects us from being overwhelmed by life events. Our species has survived because if positive or negative events distracted us too much we would not be able to get on with the business of living and surviving. In addition, if we did not adapt to things we would lose the ability to be aware of changes in our world, which is essential to survival. For example, if we were so overwhelmed by our distress we would not be able to take care of our off-spring – or if we were so delirious about our success we would fail to notice dangers and threats in life. So, at a very basic human level, our psychological and physical systems learn to adapt to good and bad things in life and we have a tendency to return to a base level of relative neutrality. This of course does not alter our ability to experience a given joy or pleasure like having a warm cup of tea on a cold day, taking a swim, or watching a sunset. We keep coming back for more once a sufficient time has passed. The rule of thumb, which you know anyway, is that spreading our pleasures over time increases the satisfaction that each produces. So the age-old adage that far away hills are always greener is shown top be true from psychological research. What far away hills do you tend to focus on in a belief that is you got what you want you would be much happier? Don’t let yourself forget the adaptation effect and consider the wisdom in the other old saying that happiness is not doing what you like but actually liking what you do. |

AuthorDr. Colm O'Connor is a Cork Psychologist. He has written hundreds of articles on family psychology - some posted here. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed