|

Today I will list small things you can do to deal with anxiety. This is not a list of how to cure or eliminate anxiety. Rather they are suggestions that can make a small change which, very often, is all you need to shift a mood or perspective.

Anxiety is a normal, predictable part of life. Everyone suffers from it to some degree while many suffer to an extreme degree. Anxiety can be a life-long companion and many people do not know what it is like to be anxiety-free. Some people experience excessive anxiety about real-life concerns, such as money, relationships, health and academics, he said. Others struggle with worry about being evaluated negatively by people. Others suffer from phobias or panic attacks. Still others have a vague non-descript anxiety with them all the time. Whatever form of anxiety you experience you can take small, effective, and straightforward steps every day to manage and minimize your anxiety. Most of these steps contribute to a healthy and fulfilling life, overall. Here are 13 small things you can do that can make a small difference. Very often a small change is all you need. 1. Breather deeply. Deep breathing triggers a relaxation response. Inhale slowly to a count of four, starting at your belly and then moving into your chest. Gently hold your breath for four counts. Then slowly exhale to four counts. 2. Walk. One of the most important things one can do to cope with anxiety is to get regular cardiovascular exercise. For instance, a brisk 30 minute walk releases endorphins that lead to a reduction in anxiety. You can start today by taking a walk. 3. Get up earlier and walk and then go to bed earlier and sleep. Not getting enough sleep can trigger anxiety. If you’re having trouble sleeping, tonight, engage in a relaxing activity before bedtime, such as taking a warm bath, listening to soothing music or taking several deep breaths. 4. Write down on a sheet of paper what you are worried or anxious about. That is all. When you write something down on a piece of paper and look at it, its importance diminishes. The if you are going to worry about them give them 15 minutes during the day when they get your full attention on the understanding that you will not give it your attention again until tomorrow. 5. Challenge an anxious thought. We all have moments wherein we unintentionally increase our own worry by thinking unhelpful thoughts. These thoughts are often unrealistic, inaccurate, or, to some extent, unreasonable. Thankfully, we can change these thoughts. Unhelpful thoughts usually come in the form of “what if,” “black and white thinking,” or “imagining the worst case scenario.” Most of the time your worry is not realistic, is unlikely to happen, and is, in any case, something you can cope with. If you are going to worry, make sure it is reasonable! 6. Don’t trust your feelings: If you feel anxious or worried do not trust it. If you feel something bad is going to happen - realise that it won’t. Anxiety creates an illusion that you fall for. It’s a magic trick that you keep falling for. Counter your naïveté by believing this: “If I feel anxious that means everything is going to be fine!” 6. Go out with friends. Social support is vital to managing stress. Talking with others can do a world of good. 7. Avoid coffee. Managing anxiety is as much about what you do as what you don’t do. And there are some substances that exacerbate anxiety. Coffee is one of those substances. The last thing people with anxiety need is a substance that makes them feel more amped up, which is exactly what coffee does. 8. Stop drinking. While alcohol might help to reduce anxiety in the short term, it often do just the opposite in the long term. Even the short-term effect can be harmful. 9. Read a Novel. Engaging in enjoyable activities helps to soothe your anxiety. For instance, today, you might start a good novel. 11. Do something small about your worry. Most people worry and ruminate but do very little. Doing anything, no matter how small, can cause a big change. If you are worried about your sister, then ring her. If you are worried about your finances, cancel some subscription or figure out a way to save €10 euro a month. 12. Accept your anxiety. If you really want to effectively manage your anxiety, the key is to accept it. Anxiety in and of itself isn’t the real problem. Instead, it’s our attempts at controlling and eliminating it. Trying not to have problems actually causes them! 13. Re-name it. Do not call it worry or anxiety – give it a better name. Call it what it is: “Catastrophising”. When talking to your husband or friend say something like: “I am addicted to catastrophic thinking”. It can help you lighten-up a little bit. Poke fun at yourself. Say to your partner “Excuse me, but I need to go to the sitting room for my fix of catastrophic thinking. I’ll be back in 20 minutes. If I look worse then its working! Keep the coffee coming!”

1 Comment

Are you anxious or are you depressed? In the world of mental health care, anxiety and depression are regarded as two distinct disorders. But in the world of real people, many suffer from both conditions. In fact, most mood disorders are a combination of anxiety and depression. Surveys show that 60-70% of those with depression also have anxiety. And half of those with chronic anxiety also have clinically significant symptoms of depression.

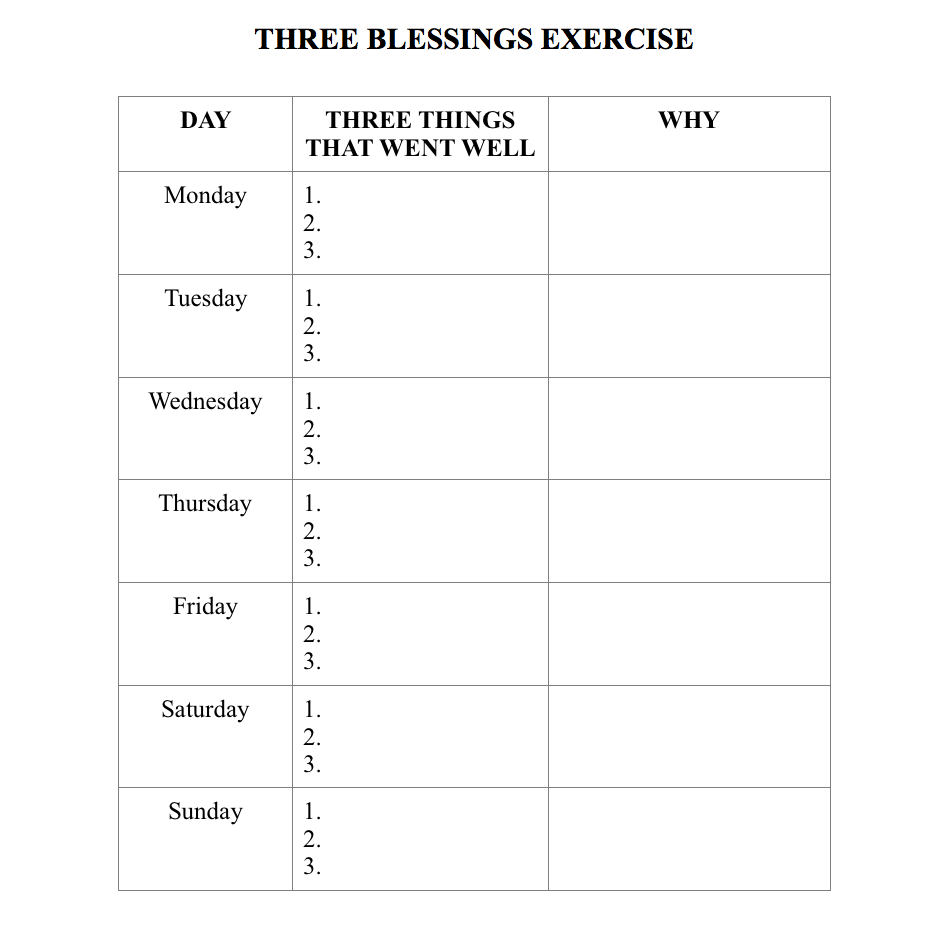

The coexistence of anxiety and depression carries some serious repercussions. It makes them more chronic, it impairs functioning at work and in relationships more, and it substantially raises suicide risk. In truth, depression and anxiety are two sides of the same coin. Researchers suggest that what goes on in the brain and body are very similar. It just seems that some people with the vulnerability to mood problems react with anxiety and some people, in addition, go beyond that to become depressed. People with depression tend to close down - it is a form of shutdown. Anxiety, on the other hand, is a kind of looking to the future, seeing dangerous things that might happen in the next hour, day, or weeks. Depression is all of that with the addition of 'I really don't think I'm going to be able to cope with this, maybe I'll just give up. It's shutdown with mental or physical slowing. Research suggests that the stress response over-reacts to situations causing anxiety and depressiveness. Negative things then tend to cause a disproportionate impact and response. You may identify with this inability to have a proportional response to situations. You may be awake at night worrying about the smallest of things, or you may feel very downcast because some small thing did not go your way. When something makes you anxious you may worry about it for a while but then begin to feel despondent that things are ever going to change. Psychologists often have difficulty distinguishing anxiety from depression. The things that work best for depression also combat anxiety. Who is at risk for combined anxiety and depression? There's definitely a family component. Looking at what disorders show up in your family history provides a clue to whether you will end up with both. If you have a lot of depression or anxiety in your family tree chances are your susceptible yourself. The nature of the anxiety also has an influence on how depressed you feel. Obsessive-compulsiveness, panic attacks, and social anxiety are particularly associated with depression as there is often no relief from the worry. Age plays a role, too. A person who develops anxiety for the first time after age 40 is likely also to have depression. Someone who develops panic attacks for the first time at age 50 often has a history of depression or is experiencing depression at the same time. Usually, anxiety precedes depression, typically by several years. Currently, the average age of onset of anxiety is late childhood/early adolescence. This actually presents an opportunity for the prevention of depression, as the average age of first onset of depression is now mid-20s. A young person is not likely to outgrow anxiety unless he/she learns some mental skills. But dealing with anxiety when it first appears can prevent the subsequent development of depression. The cornerstone of anxiety and depression is overestimating the risk in a situation and underestimating personal resources for coping. Those vulnerable see lots of risk in everyday things-applying for a job, asking for a favour, asking for a date. They also doubt that they have the abilities to deal with these situations and can withdraw. Further, anxiety and depression share an avoidant coping style. Sufferers avoid what they fear instead of developing the skills to handle the kinds of situations that make them uncomfortable. Often enough a lack of social skills is at the root. In fact the link between social phobia and depression is dramatic. It often affects young people who can't go out, can't date, don't have friends. They're very isolated, all alone, and feel cut off. A simple question to ask yourself if you are suffering from anxiety/depression is “ What am I avoiding?” “What do I need to do with my life, my marriage, or my work that I have really been avoiding doing? What decision may I be avoiding that leaves me desperately worried or gloomy?” Whatever the situation, the twin problems of anxiety and depression can become very debilitating as you feel increasingly helpless to do something about the problems you worry about. So you go around in circles and find it very difficult to create positive momentum with your life. The best thing you can do for now is to tell someone, to admit to your problem and to your helplessness. To give it a name. To get help. To help yourself. Depression is a nasty and debilitating disorder. When it is severe, there are four sets of symptoms: a chronic sad fatigue, a sense that the future is dreary, a sense of helplessness, and a loss of positive appetites. The field of psychology and psychiatry have tried to treat depression for many years with antidepressant drugs and or counselling. The success of treatments tends to be confined to moderate relief in about 65-70% of cases. Embarrassingly for our profession, placebos (that is when someone thinks they are getting a drug but are in fact getting an aspirin) have a 45-50% success rate! For those of you suffering from depressiveness, what can you do? Well Martin Seligman has just reported a fascinating piece of research, the pioneer of positive psychology, regarding what one can do to make a difference to depression. They did research on the effectiveness of completing the simplest and most uncomplicated of tasks. It was simply this: Depressed people were required to write down three things that went well that day and why they went well. That’s all. Nothing more. No counselling. No drugs. No talking. Just write down three blessings. It was called the THREE BLESSINGS exercise. They had to do it for one week. Here are the results. 50 severely depressed people participated in the study. At the end of that week 47 of them reported being far less depressed. In terms of overall happiness, 46 of the fifty people increased their happiness significantly. These results were actually better than a comparable group who took drugs or received counselling! Now before we run away with ourselves with this, there is a lot more research that needs to be done to examine the validity of these findings, but they point to something critical to everyone struggling with depressiveness. What we can learn from this is simple – there are positive and simple things you can do on a daily basis to change your mood. The THREE BLESSINGS exercise may seem hoaky, or trivial. You might, like a lot of people, justify your depressiveness by saying such things as “I am such a complicated person that a simple change wont do much for me.” “My depressiveness is very deep and a result of a lot of bad experiences, so changing is going to be very difficult for me.” Or “Things like that might wok for other people, but I am different.” Such thinking is not helpful. What we find is that major changes are a consequences of small one’s. Small changes can change big systems quite dramatically. Take the metaphor of the log-jam. You will have experienced this in traffic when one car can cause a back-up of up to a hundred cars because it has manoeuvred its way badly up Barrack Street, Blarney Street, or Sunday’s Well. However, to let the traffic flow correctly again may mean only a small change. If one car reverses a few feet and allows another one through the entire traffic jam can be released. In other words what can look like a huge traffic problem can be freed up by a small change. It’s the same with changing one’s life. One small change can have a huge effect on the flow of your emotional life. I sat with a young woman this morning that has been suffering from depression. We sat down for an hours and wrote out a list of all her goals and objectives for the next two years. At the end of our session she had a list of about 50 things she would have to do to achieve her dreams over that time. She was thrilled because when she came in she felt that there was no focus to her life, and nothing to get out of bed for. However, though it was a relatively simple task to do what I had done, this girl had never in her life taken an hour to think in a disciplined to convert her dreams into goals and to convert her goals into easy-to-do objectives. Discipline is Depression’s most feared opponent. Why not try the Three Blessings exercise and see what happens. Blue-tack a sheet of paper to your bedroom wardrobe with the following grid: Don’t be so proud or cynical to think that you are above such simplicity of living. Count your blessings. You, and they, deserve it.

There is an old saying that suggests that: “If you want to be happy for a few hours, get drunk. If you want to be happy for a few years, get married. If you want to be happy forever, get a garden!” The wisdom of this is in emphasising that the simplest of activities can often produce the most enduring happiness. Much of the research on the topic of happiness produces results that are not surprising but listed are a few of the more interesting findings. For example, most of us want to win the Lotto and believe that we would be much happier and content if we did. Research shows that this does not actually happen. As some of the points below illustrate, most of us have a relatively set range or happiness level that does not change too much throughout life. Our mood fluctuates form situation to situation, and may be elevated or diminished for longer periods as a result of life circumstances, but most of us return to our own base level. You will notice this with people you know - how their personalities are relatively stable and, despite life circumstances and events, they pretty much stay in character. Research shows that even the most dramatic changes often have little effects on these base levels. So, forget about pining for the Lotto, its effects would last about three months after which you would be back to your same-old self. What we can do however is to find out what we are like when we are at our best, what makes us feel good and content, and to do more of those things. Learning to be happy means learning to understand your personality, your character strengths, and those activities that bring out the best in you. Then, the formula is very simple: Use your strengths and do more of what makes you feel good. It may be as simple as gardening, taking a walk, reading a book, having a regular holiday, or concentrating on a simple hobby. So, think of activities you do that represent you at your best, at your most content and happy, and at your most vibrant. Then decide to build these activities into your life with regularity! Here are some other interesting research findings on happiness:

The moral of the research: Happiness can be taught! It should be a compulsory class in all schools – i.e. learning the science of well-being. The case of the helpful motorist:

Hers is an interesting piece of research I came across recently, which shows that kindness and observing others engaged in helping learns helpfulness. Those of you with children will be aware that small children who might help carry groceries from the car might also want to help in putting them away. This piece of research shows that setting an example has a strong effect on people’s helpfulness. This is called the modelling effect – that is the effect of watching someone else modelling what should be done. The surprising thing is that is as applicable to adults as it is to children. A researcher called Bryan, from Ontario, investigated whether motorists were more likely to help a woman change a car tyre if they had earlier seen someone else doing a similar act. He set up two situations where he would test motorists without them being aware that they were being tested: In one situation motorists first passed a woman whose car had a flat tyre; another car was pulled to the side of the road and the male driver was pretending to help her change the tyre. This situation provided a helping example for those motorists who, two miles later, came upon another car with a flat tyre. This time the woman was alone and needed assistance. In the second situation, only the second car and driver were present; there was no illustration or pretend model. The results were clear. The motorists who were exposed to the situation of the man helping the woman were twice as likely to help when compared with the other motorists. What this illustrates is simple, no matter what age you are you are still stimulated to help others by seeing other people being helpful. Or to put it another way, by you being helpful to others you automatically make it easier for others to be helpful. This is a simple but quite profound fact. In studies of the effects of viewing what is termed pro-social behaviour (rather than antisocial behaviour) on television, the conclusion from research is that children’s attitudes toward positive behaviour are improved. Learning pro-social behaviours has a positive effect all-round on a child: Research shows that when children are exposed to pro-social behaviour they are more likely to delay their own gratification – e.g. in sharing their sweets, in waiting for a slow child, in re-starting a game for someone who misunderstood the rules, etc. Furthermore research also shows that that children who exhibit such behaviour are more popular with their peers. Other research on happiness has shown that one’s happiness in life increases as a consequence of engaging in pro-social behaviour. For example, if each week, you made a point of meeting with someone who is important to you in your life and used that meeting to convey your genuine gratitude to them for what they have meant to you, your general contentment and happiness would improve. The meaning of this for us as parents to be sure that, no-matter what they are like, we should engage children positively in helping behaviours toward family, friends, neighbours. This is more than just telling them to be nice or mannerly. It would be more beneficial to get your child to help you in a positive way with a particular helpful behaviour: to help an elderly neighbour mow her lawn, to write and deliver a letter to a person in need, to conduct one random act of kindness a week for anyone. Again, the research is simple in its conclusions: either witnessing or participating in helpful and kindly behaviour generates more of the same in the heart of the helper, and in those affected. So if you are feeling down today, for whatever reason, consider that you might find relief by helping someone else rather than yourself. You grow up thinking there is something wrong with you. As years go by you develop the endless habit of reminding yourself of your inadequacy. At school and at home you begin to believe that there is something defective in you. The big secret however is that you are not inadequate and there is nothing wrong with you.

The process of socialization teaches us:

Socialization and growing up does not tend to teach us:

So by the time socialization is complete, most of us hold an UNSHAKABLE BELIEF that out only hope of being good and effective in life is to punish ourselves when we are bad. This is what Freud called our superego - our inner mental Judge that punishes us continually for our misdemeanors. We come to believe that without punishment our badness would win out over our goodness. Without constantly criticizing ourselves for our failures we would become slothful, lazy, and deteriorate into the mud of mediocrity. The thing is: None of this is true! If we were to move from self-punishment and self-rejection to self-encouragement and self-acceptance we would thrive. To be encouraging and accepting of ourselves we must learn to befriend our glorious imperfection. To realise and accept that in our ordinariness we are most truly human. To be utterly compassionate toward our self, to be tolerant of our inadequacies, and to allow ourselves to be the same as everyone else we take a first giant step towards selflessness. We get a glimpse of what it is like to be free of self-judgement and we begin to flow. The battering cycle of Domestic Self-Violence, for want of a term, starts with the pressure we place on ourselves to be perfect. This leads to stress which results in coping behaviours such as competing with others, giving ourselves a hard time, trying to motivate ourselves, drinking or overeating, etc. All of this allows us to feel better for a very short time followed by feeling a whole lot worse. This results in our punishing ourselves again for being inadequate, imperfect, or for failing. So what do we do? We decide to be perfect again, to set new standards and start with a clean slate and new goals. And the pressure and stress to be perfect kicks in again. This is a cycle of battering in which we abuse our selves. Personal development does not begin until these beatings stop. In counseling what people tend to find most helpful is having a time during which you stop battering your self. To stop battering and punishing yourself takes is as much a spiritual task as it is a psychological one. To become a person who is compassionate toward oneself takes a meditative almost prayerful disposition. In psychology we call it mindfulness. In Buddhism they might call it meditation. In Christianity it is encountering the sacred within. The only way out of a life of daily irritation with oneself is through the doorway of compassion. The skills and discipline needed to counteract the automatic irritation you feel about your imperfection must be practiced with an open-heart and a determined will. Forget about your Carbon Footprint - What is your Compassion Footprint? Cognitive psychologists have been studying self-esteem for decades. They have identified thirteen kinds of mental distortions that people use that result in negative feelings. There are 10 ways to feel bad about yourself. Spot your most commonly used distortion and consider how it affects how you feel about yourself:

2. Shoulds, musts, oughts. These are the demands we make of ourselves. For example, “I should have known better”, “I should be more efficient with my life”. We think that we motivate ourselves with such statements when in fact they make us feel worse. 3. The fairy-tale fantasy This means demanding the ideal from life. This kind of expectation results in feeling things are not fair or feeling a victim of circumstance. The fairy-tale fantasy is one where life should be ideal, without pain, suffering, or failure. The reality is that everyone has to carry the unavoidable burden of such experiences. When you measure your life against the ideal life you inevitably feel disappointed or stressed-out. 4. All or nothing thinking This kind of thinking is when things are either a complete success or a total failure. You hold yourself to the impossible standard of perfection and when things fall short of it you conclude that it was a total disaster. You might assume that just because one person does not like you at work, that work is therefore intolerable. If you cannot give yourself between 95 and 100% in your how-I-did-today score, you feel you have failed. Try to see that a score of 75% is very good, and with such a score you are entitled to feel very good about yourself! 5. Over-generalizing This is when you decide that a particular negative experience should be generalised to your entire life. For example, “I always ruin everything”; “I always make a mess of things”; “I never do well in maths”. Such global statements make generalizations from specific incidents to everything else which is unkind and always inaccurate. Instead of saying “I can never cope with being a parent”, say, “Sometimes I cannot cope, but overall, I am doing okay”. 6. Name-calling Here you give yourself a label, which is a form of name-calling. You will say to yourself that you are ugly, stupid, awkward, boring, uninteresting, etc. The truth is that you care so much more than what your name-calling of yourself. You are usually only about 5% right in what you say. 95% of you is very different. Putting yourself down in such derogatory ways should not be acceptable. You would not treat another person that way, why do it to yourself? 7. Obsessing When you obsess about the negative you go over and over the same unpleasant incident that either has happened or might happen. This distortion makes you re-run action replays of unpleasant incidents over and over again. Or else it runs action pre-views of the mistakes you expect to make. Instead of obsessing about unpleasant incidents that you imagine will occur, try running previews in your head of the positive experiences that can happen. 8. Rejecting the Positive90% of your daily events could be described as positive, 1% might have been negative, with the other 9% as neutral. However, what the person with poor self-esteem will do is react to themselves as if it was 95% negative and 1% positive. Most people have a tendency to do this. For one day, see if you can give yourself credit for all the small successes you achieve. Went to the shop, tidied out the cupboard, phoned Mom, made a lovely dinner, showed sympathy to a neighbour, posted those bills, had 20 minutes with my sister, read a nice piece in the paper, spoke to husband about the holidays, made out a Christmas list, etc. Instead of giving yourself a zero on all of these – give yourself one unit of credit in your self-esteem bank where ten units equal a GREAT DAY! 9. Personalizing In this instance you see yourself as much more involved in negative events than you really are. You make be taking all the responsibility for your teenagers bad moods, or may feel responsible in some way because your husband is under stress, or may feel unable to get everything done at work. Think again. You may have some influence on things but you are not the cause! Ask yourself, am I the cause of this or do I just have some influence, along with a lot of other influences? 10. Soap-opera-ing In this instance you turn an unpleasant event into a catastrophe. You convince yourself that something is so overwhelming that you cannot cope with it. “I cannot cope with my children!” “I cannot handle the fact that I am so shy”; “If that happens, I will literally fall apart”. Some people create enormous dramas in their head where difficult situations are dramatised into soap-opera’s over which they feel they have little control. Remember, today is the tomorrow you worried about yesterday. Burnout is often hard to detect for the simple reason that to admit to burnout is to admit to some element of helplessness. Most people who suffer burnout are the last people to notice it because they may cling so tightly to a hope of a goal. Burnout happens when people who have previously been highly committed to something lose all interest and motivation. Typically it refers to one’s job but it can equally apply to an intimate relationship or to the tasks of parenting. I will talk here about job burnout but as you read, “think” relationship or parenting if you wish.

Sadly, burnout can mark the end of a successful stage in one’s career. It mainly strikes highly-committed, passionate, hard working and successful people – and it therefore holds a special fear for those who care passionately about the work they do. Burnout is a state of undetected exhaustion caused by long term involvement in emotionally demanding situations. It includes the frustration brought about by devotion to a cause, way of life, or relationship that failed to produce the expected reward. Burnout therefore involves both exhaustion and disillusionment. Anyone can become exhausted. What is so poignant about burnout is that it mainly strikes people who are highly committed to their work: You can only "burn out" if you have been burning with light in the first place. While exhaustion can be overcome with rest, a core part of burnout is a deep sense of disillusionment, and is not experienced by people who can take a more detached view of their work. Psychological research has looked at the way in which animals handle long-term stress. What it shows is that after an initial period of adaptation, they survived very well for quite a long period of time until, then all of a sudden, their resistance collapsed without any obvious direct cause. A similar process was seen with bomber pilots in the Second World War, who would fly effectively for many missions, but who would then fall apart as pilot fatigue set in. We have probably all seen similar patterns in the past, where people become exhausted and their performance suffers. We may all have worked so hard at something, for so long, that the easy things become difficult and life loses its flavour. These are times when rest (often in the form of a good holiday) helps us to approach the situation with a new vigour. Exhaustion and long-term stress contribute to burnout, but they are not the most destructive parts of it. The real damage of burnout comes from the sense of deep disillusionment that lies at its heart. Many of us get our sense of identity and meaning from our work. We may have started our careers with high ideals or high ambitions and may have followed these with passion. This is easy to see in doctors and teachers, who may have a strong desire to help other people to be the best that they can be. But it can happen to everyone – from the person devoted to a family business to a floor worker who sets off trying to do a good job. Others may be ambitious for promotion or may want to “make a difference” to people or organizations in some other way. In all of these cases, these ideals can drive a highly motivated, passionate approach to work. It is incredible what we can achieve when we truly believe in what we are doing: We are hard working, effective, full of initiative, energetic and selfless. We can find ourselves doing much more than we are contracted to do, working much longer hours. Even more, we enjoy doing this. We find it easy to enter the hugely satisfying state of flow. Particularly when we are appreciated for what we do, and when we are able to see good results from our work, this satisfaction can help us to overcome enormous difficulties. It is not surprising that people showing this level of resilience and commitment to their work are often spectacularly successful. The problem comes when things become too much. Perhaps exhaustion sets in because people have been working too hard for too long. Perhaps performance begins to slip because of this. Perhaps the problem being solved is too great, and the resources available are too meager. Perhaps supportive mentors move on and are replaced by people who do not appreciate the heroic job that is being done, or do not subscribe to the ideals that drive performance. Perhaps co-workers or team members make just too many emotional demands, or people being served prove to be ungrateful and difficult. Being proactive, energetic, committed people, it is likely that we respond to obstacles like these by increasing our commitment and hard work. However, in these circumstances it is possible that these efforts may have little or no impact on the situation. This can be where burnout begins to set in. As we get less satisfaction from our jobs, the downsides of these jobs become more troublesome. As we get more tired, we have less energy to give. If our organizations fail to support us, we can get increasingly disenchanted with them. We become increasingly disillusioned. In extreme cases, we can lose faith completely in what we are doing, and what our organizations are doing, becoming cynical and embittered, and feeling that our ideals and meanings in life count for nothing. This is full-scale burnout. It is most revealing to observe how so-called rational people behave in long-term intimate close relationships. In some embarrassing ways, most grown ups literally act like babies when they are in the throes of relationship conflicts. Let me explain: There are three basic beliefs that influence our behaviour as adults that have their origin in very early childhood.

The first of these beliefs is that “If I cause you enough distress you will give me what I want!” This belief influences most people in adult relationships. There is hardly a reader who does not try to get what they want or need by creating some form of distress for the potential giver. In marriages this includes such behaviours as nagging, whinging, complaining, persistent requests, sulking, etc. The idea is that if I make my partner upset enough he or she will give in to me and provide what I need. This belief is of course the essential survival strategy of the newborn infant. The cry of a small baby is uniquely designed to get the attention of the mother and to distress her so much that he or she is impelled to take action. When you think of this from the perspective of evolution and survival you will appreciate that a baby that does not do this will get ignored. So if a baby has a wet nappy, is hungry, or is in pain he/she creates minor distress by crying that results in the mother coming and rectifying the problem. Adults, in trying to get their needs met, very often do the same thing. People operate on the belief that “If I annoy and pester my partner enough then he/she will eventually give me what I want!” It’s crazy when you think of it this way, but it is nonetheless a strategy of choice for many. Because people have this internal program that impels them to ‘act like babies’, most people find it hard not to. So grown men whinge, complain, and sulk. Grown women nag, wear-down, and flood their partners. There is a second common belief that has its origins in infancy which you probably also do. This belief is that “You should know exactly what I need without my having to explain it to you.” In infancy every child has to operate on this assumption. Small babies cannot explain to their mothers exactly what is wrong with them; the mother or caretaker has to figure out what the need is and then to rectify it. Whether its hunger, soiling, tiredness, or discomfort – it is up to the mother to figure it out. We also do this in adulthood. Most people still carry that belief that they should not have to explain things to their partner and grow resentful if they have to. Most people carry this childlike expectation that, in an intimate relationship, they should be able to relax back and have their needs understood and catered for. In fact the rage and resentment that erupts when a spouse discovers that their partner does not have a clue what they need, is indeed most intense. How often have we heard the refrain that “if I have to explain to you what it is that I want then there is no point in even asking in the first place!”? Unfortunately love cannot always be like that, but our infantile beliefs have us almost convinced that it should. The third belief that we hold is that “If I am not getting my needs met then the reason for this is that my partner is withholding it!” This belief operates on the assumption that the reason that your husband or partner does not love you properly is because he is stubbornly withholding what you want and need. This belief automatically results in angry attempts to coerce the person into handing over that which they withhold. I have seen couples caught in this pursuit for 20 years. The alternative conclusion, that he/she does not have it in the first place, is a scarier one and often not considered by the frantic mate. Again, it has parallels in infancy because the little baby has no option but to operate on the belief that the mother or carer has what they need. Hence the little innocent will cry for hours waiting for the mother to come and rescue them. However, it does not work in adulthood. In fact, in adult relationships the carer tends to withdraw further in the face of such demands. The message for today is to remember how childlike we all are and though we like to portray ourselves as being imminently reasonable, in the confines of our close relationships we reveal an innocence that is all too humbling. |

AuthorDr. Colm O'Connor is a Cork Psychologist. He has written hundreds of articles on family psychology - some posted here. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed